The controversy surrounding the release of Deepa Mehta’s film, Funny Boy, a cinematic adaptation of the original 1994 novel written by Shyam Selvadurai, prompted me to read the original book. Funny Boy is a coming-of-age story centered on Arjun Chelvaratnam, chronicling his life in the form of six short stories linked by his self-discovery in a world shaped by cultural rigidness and political turmoil.

Arjun Chelvaratnam, affectionately called Arjie, comes from an upper-crust Tamil family residing in Colombo, Sri Lanka. He and his two siblings, Varuna (nicknamed Diggy) and Sonali, luxuriate in a life far more privileged than most children on the island-nation. And yet, because of their ethnic background, they’re taught from an early age to tread carefully.

In the first of six stories, Arjie is a eight-year-old child in 1970’s Sri Lanka. Twenty years had passed since the infamous ’58 riots, in which a pogram targeted Tamils, killing hundreds of people, including Arjie’s paternal grandmother’s father, leaving Arjie’s grandmother, whom he called Ammachi, with a deep-seated hatred for the Sinhalese. Arjie’s father, Chelva, was also affected but he took a different approach. Chelva reasoned that Sinhala was the future of the island. He enrolled his children in Sinhala classes and even declined to speak to them in Tamil. Thus, Arjie practically grew up removed from his Tamil heritage, and yet his Tamilness differentiated him like the Mark of Cain throughout his upbringing on the island-nation.

It wasn’t just Arjie’s Tamilness that would set him apart from his peers. The first story, “Because Pigs Can’t Fly”, begins with a game of bride-bride. The female cousins of the extended family would reenact a wedding, each of them playing different roles. The least-coveted role was the groom, perceived by the girls as boring but necessary in a wedding. However, in the opening passages of “Because Pigs Can’t Fly”, the bride is played by none other than Arjie. While the other boys, along with the presumably tomboy Meena, would play cricket, Arjie would join Sonali and the other girls and play games like bride-bride. As the bride, Arjie reveled in dressing himself up in an embroidered sari, and decorating his face with red lipstick and mascara. Arjie may not have been transgender but he clearly enjoyed defying gender expectations.

Unsurprisingly, Arjie’s parents, along with other relatives, didn’t see it the same way. After a fight with a disgruntled cousin name Tanuja, whom he and the others cruelly called “Fatty”, Arjie, clad in his bridal wear, was brought by his aunt, Tanuja’s mother, to be shamefully paraded before his aunts, uncles, grandparents and, embarrassingly, his parents.

“Hey, Chelva! You got a funny one, here”, Arjie’s uncle, Cyril, teases. However, Arjie’s father would not even look at his dressed-up son, presumably out of horror and humiliation. Throughout the novel, Chelva constantly worries about his son’s “masculinity”. He’s petrified over the thought of his son turning out “funny”, similar to one of their neighbor’s sons. So he diligently does all he can to instill traditional masculine sensibilities in his younger son. However, it’s evident that nature has the bigger stick in this fight.

Throughout his upbringing, Arjie identifies more with his female family members and relatives than his male relatives. For example, while he and Diggy have a somewhat terse relationship, due to having nothing in common, Arjie is intimately close with his sister, Sonali. While he and his father don’t see eye-to-eye, Arjie gets more sympathy from his mother, Nalini. In fact, despite the fact that she has a daughter, Nalini only allows Arjie to watch her as she dresses up in her sari ( at least, before Arjie was reprimanded by his father for playing bride-bride). And while Arjie isn’t close with any of his uncles, he develops a very intimate relationship with his father’s youngest sister, Radha.

Remarkably, at a young age, Arjie is twice-recruited as an accomplice in the clandestine dalliances of his female family members. The first time involves his Radha Aunty, who’s engaged to a Tamil engineer residing in Canada but falls in love with a young Sinhalese stage actor whom she and Arjie met while performing for a play. The second time, startlingly, involves his own mother. Although she doesn’t spell it out for her son, Nalini engages in a brief affair with a childhood friend, whom she was barred from marrying due to their differing ethnic backgrounds. She uses her son’s temporary illness as a scapegoat to carry out the fling in the central hills of Sri Lanka, away from the city. That affair ends in tragedy and reshapes Nalini’s perspective on the emerging Tamil insurgency and Sri Lanka’s political strife.

Both secret affairs illustrate the clash between the personal and the political. Similar to novels such as Arundhati Roy’s The God of Small Things, Funny Boy highlights the futility of forbidden love and how quickly it’s usually stifled by unwritten social codes, boldened by political conflicts. It demonstrates how the individual pursuit of personal fulfillment and happiness is often extinguished by social forces beyond one’s control. The anticipated termination of both affairs foreshadows Arjie’s own clandestine encounter.

The fifth short story, “The Best School of All”, centers on Arjie’s enrollment at Victoria Academy, a British-style, all-boys prep school. Chelva forces Arjie to attend Victoria Academy in hopes that that it would quench his lingering “funny-boy” tendencies. Ironically, Victoria Academy is where Arjie comes to terms with his homosexuality and engages in a secret fling with another male student named Shehan. So, for Chelva, that was a major swing-and-a-miss!

Victoria Academy is administered by a strict principal who is only referred to as “Black Tie”. Black Tie is an iron-fisted, traditionalist overseer of the campus community. He makes it his objective to ensure that his students are well-disciplined and properly-attired, according to his standards. For example, he shows no tolerance for Shehan’s long hair and often calls him and the other “miscreants” as “future ills and burdens of Sri Lanka.” Any schoolboy with freeze in fear of Black Tie’s presence and relentlessly curse him once he is out of the room.

And yet, the narrative forces you to sympathize with Black Tie. As principal, Black Tie has a acrimonious working relationship with the school’s vice-principal, Mr. Lokubandara. Lokubandara is an ambitious Sinhalese man who’s politically well-connected. His aspiration is to take over Black Tie’s position as principal and transform the school into a Sinhalese Buddhist institution, cutting ties from its British colonial and multiethnic roots. Although he is often mild-mannered, he unhesistantly gives preferential treatment to the Sinhalese students. In contrast, despite Black Tie’s unpleasantness, his goal is to maintain Victoria Academy’s multiethnic makeup and ensure that all students, regardless of ethnic background, are treated fairly.

The conflict between Black Tie and Lokubandara symbolize the cultural clash that emerged after the British left the island. One side wanted to maintain the national identity of a multiethnic island-nation. The other side wanted to enforce a Sinhalese-dominant national identity. In the narrative, as in the real world, one side had eventually won.

Arjie is caught in the middle of conflicting interests. He is recruited by Black Tie to recite two poems for a ceremony featuring a prominent politician. Black Tie stresses that his competence in reciting the poems will determine whether Black Tie can keep his job and ensure that Victoria Academy remains a multiethnic community. As a Tamil student frequently bullied by the Sinhalese students in the school, Arjie undoubtedly sympathizes with that cause. However, Black Tie had also been the bane of Arjie’s existence, mostly because of his tortuous treatment of his lover, Sheheen. So, Arjie once again finds himself in the fissures of the personal and the political.

Funny Boy is a gripping yet extremely heartbreaking novel. As aforementioned, the narratives highlight the futility of forbidden love in addition to the dire inevitability of ethnic violence. The recent cinematic adaptation of the novel did not do justice to the themes conveyed by the short stories. The movie depicts the ethnic conflict as a tit-for-tat battle between the Tamils and the Sinhalese. However, the novel reveals that the persecution of the Tamils was systemic endeavor undertaken by the Sinhalese-dominated state apparatus. The erroneous framing of the conflict in the movie undermines the reasons why thousands of Tamils left their homeland.

Funny Boy was published in 1994, a time when homosexuality was recognizable in mainstream society, but gay people were still derided. The author, Shyam Selvadurai, is a gay man himself who grew up in Sri Lanka during the 1970’s and 1980’s. Although the novel is not autobiographical, the experiences and inner turmoil of Arjie is undoubtedly a (partial) reflection of Selvadurai’s own experiences. Our society has come a long way since that era. We’ve become more accepting and compassionate. However, even today, there are teenagers, like Arjie, who struggle to grasp their sexual identities.

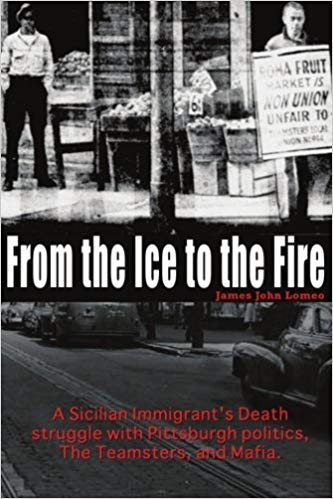

Since arriving in the New Country, Paulo Lomeo’s life was filled with happiness and productivity. After a few weeks in the United States, he serendipitously met his future bride while buying a sandwich with whatever loose change he had in his pocket. His marriage to Rosalia, an American-born Italian woman, proved to be the rock in his life, as Rosalia continuously provided unconditional support for her husband in whatever tumultuous circumstances in which they found themselves. After settling in the Mckeesport, a suburb of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, Paulo adopted the American entrepreneurial spirit by starting his own business, Roma’s Fruit Market. While Paolo’s business didn’t elevate him to the corporate elite class, he managed to earn a respectable livelihood for himself and his family. All in all, Paulo had achieved the American Dream.

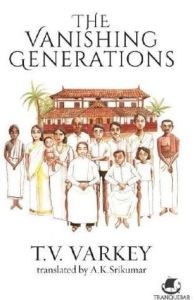

Since arriving in the New Country, Paulo Lomeo’s life was filled with happiness and productivity. After a few weeks in the United States, he serendipitously met his future bride while buying a sandwich with whatever loose change he had in his pocket. His marriage to Rosalia, an American-born Italian woman, proved to be the rock in his life, as Rosalia continuously provided unconditional support for her husband in whatever tumultuous circumstances in which they found themselves. After settling in the Mckeesport, a suburb of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, Paulo adopted the American entrepreneurial spirit by starting his own business, Roma’s Fruit Market. While Paolo’s business didn’t elevate him to the corporate elite class, he managed to earn a respectable livelihood for himself and his family. All in all, Paulo had achieved the American Dream. The Vanishing Generations is the English translation of the Malayalam novel, Manjupokunna Thalamurakal, written by T.V. Varkey. It’s a multigenerational tale that centers on the Paalat family, a Malayali Syrian Catholic clan. The novel opens in Kudumon, a small village situated on the Malabar Coast, during the 1850’s. Our first lead character, Kunjilona, of the Cholkunnu house, is arranged to marry Mariamma, the only daughter of a widow named Thandamma. Mariamma is from the Paalat house, a clan notorious for an alleged curse resulting in the deaths of its sons-in-law. In the Malayali Syrian Christian community during the 19th century, it was customary for families without male children to adopt the husbands of their daughters. Therefore, following his marriage to Mariamma, Kunjilona left the Cholkkunu house and formally joined the Paalat clan. Despite anticipation of an untimely death from marrying into the Paalat House, Kunjilona manages to live long enough to start his own business and raise a family of his own. Kunjilona’s success raises the status of the Paalat House to a level of respectability and prestige.

The Vanishing Generations is the English translation of the Malayalam novel, Manjupokunna Thalamurakal, written by T.V. Varkey. It’s a multigenerational tale that centers on the Paalat family, a Malayali Syrian Catholic clan. The novel opens in Kudumon, a small village situated on the Malabar Coast, during the 1850’s. Our first lead character, Kunjilona, of the Cholkunnu house, is arranged to marry Mariamma, the only daughter of a widow named Thandamma. Mariamma is from the Paalat house, a clan notorious for an alleged curse resulting in the deaths of its sons-in-law. In the Malayali Syrian Christian community during the 19th century, it was customary for families without male children to adopt the husbands of their daughters. Therefore, following his marriage to Mariamma, Kunjilona left the Cholkkunu house and formally joined the Paalat clan. Despite anticipation of an untimely death from marrying into the Paalat House, Kunjilona manages to live long enough to start his own business and raise a family of his own. Kunjilona’s success raises the status of the Paalat House to a level of respectability and prestige.

ra Kapoor, a young model, and Shiv Natraj, a retired professor, as they cope with the pain of their respective spouses being in a coma. Despite their radically different personalities and contrasting worldviews, the two find solace in each other, as they are the only ones who can understand what the other is feeling.

ra Kapoor, a young model, and Shiv Natraj, a retired professor, as they cope with the pain of their respective spouses being in a coma. Despite their radically different personalities and contrasting worldviews, the two find solace in each other, as they are the only ones who can understand what the other is feeling. Naseeruddin Shah, as a veteran of Arthouse cinema, was perfect for his role. Kalki Koechlin also did remarkably well. She successfully managed to convey the distress of a woman who practically lost her husband without being excessively melodramatic. The supporting cast, including Rajat Kapoor as the physician, also did exceptional.

Naseeruddin Shah, as a veteran of Arthouse cinema, was perfect for his role. Kalki Koechlin also did remarkably well. She successfully managed to convey the distress of a woman who practically lost her husband without being excessively melodramatic. The supporting cast, including Rajat Kapoor as the physician, also did exceptional.

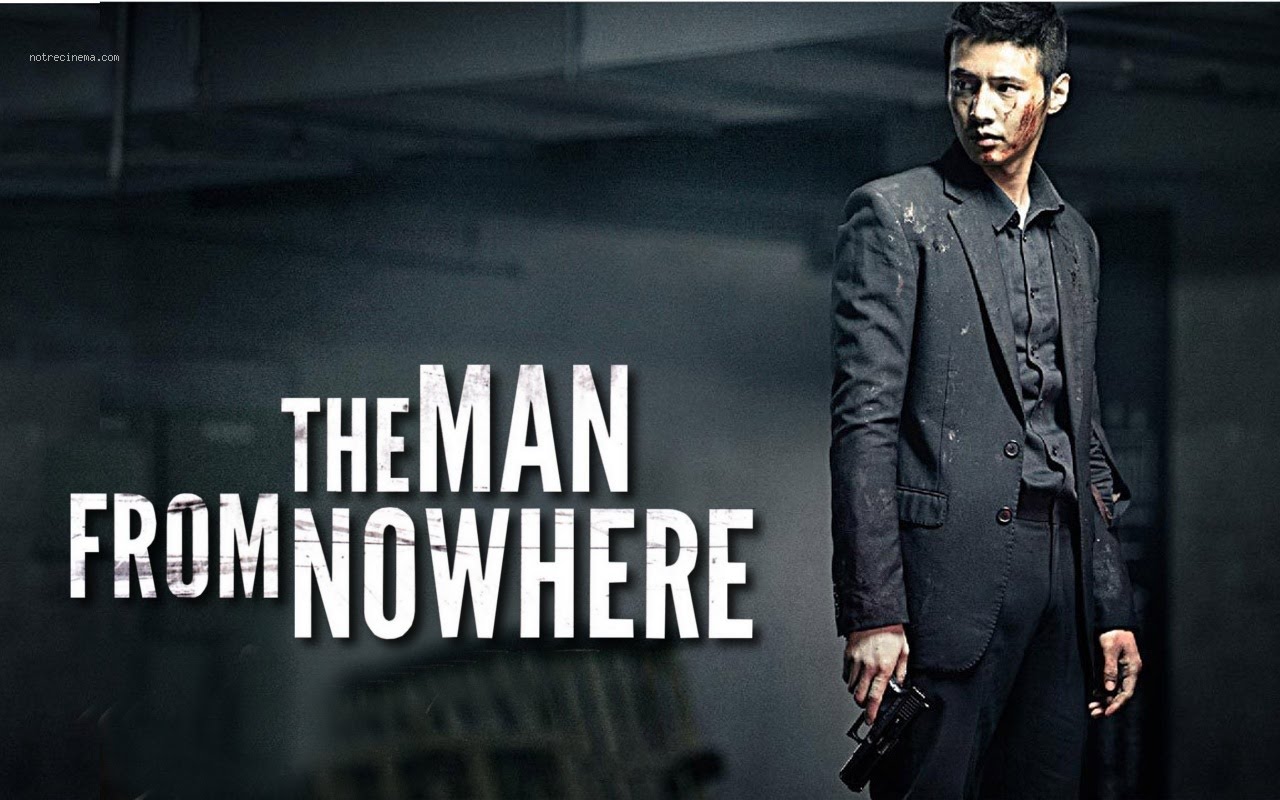

only daughter. Detaching from her mother, So-mi turns to her neighbor, Cha Tae-sik, and invests all of her affection towards him. When So-mi infers Cha Tae-sik’s seemingly apathetic attitude towards her, she laments:

only daughter. Detaching from her mother, So-mi turns to her neighbor, Cha Tae-sik, and invests all of her affection towards him. When So-mi infers Cha Tae-sik’s seemingly apathetic attitude towards her, she laments: unabashedly retains her love for Cha Tae-sik because that is her source of sustenance and hope. Her love for Cha Tae-sik is the net preventing her from falling into the abyss of nihilistic despair.

unabashedly retains her love for Cha Tae-sik because that is her source of sustenance and hope. Her love for Cha Tae-sik is the net preventing her from falling into the abyss of nihilistic despair. exceptionally menacing as Man-Seok, from the crime syndicate.

exceptionally menacing as Man-Seok, from the crime syndicate.

Trance, directed by Anwar Rasheed and written by Vincent Vadakkan, is a story about a simple man named Viju Prasad. All that Viju, portrayed by Fahadh Faasil, wants is to be a world-acclaimed speaker, with thousands of people heeding this words. He relishes this aspiration, clapping to himself in front of a mirror in anticipation of the thousands of pairs of hands applauding in praise of him. And yet, this man is also shackled by the dire toments of his own life. His mother’s suicide left him and his younger brother, Kunjan, orphaned. Kunjan’s tortuous battle with depression, which also resulted in suicide, has darkened Viju’s outlook and hopes. And lastly, Viju is chained to his own psychological issues, which leaves him vulnerable to be manipulated for a sinister scheme.

Trance, directed by Anwar Rasheed and written by Vincent Vadakkan, is a story about a simple man named Viju Prasad. All that Viju, portrayed by Fahadh Faasil, wants is to be a world-acclaimed speaker, with thousands of people heeding this words. He relishes this aspiration, clapping to himself in front of a mirror in anticipation of the thousands of pairs of hands applauding in praise of him. And yet, this man is also shackled by the dire toments of his own life. His mother’s suicide left him and his younger brother, Kunjan, orphaned. Kunjan’s tortuous battle with depression, which also resulted in suicide, has darkened Viju’s outlook and hopes. And lastly, Viju is chained to his own psychological issues, which leaves him vulnerable to be manipulated for a sinister scheme.